Written by Julianna Wu, AJ Cortese

An uncertain regulatory environment in the US is prompting mature Chinese tech companies to hedge a secondary listing in Hong Kong.

The United States’ Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act was signed into law in December 2020. It subjects foreign companies listed on US stock exchanges to more stringent accounting standards, and failure to comply with the legislation within three years could result in a company being delisted. While the law applies to all foreign companies that have ticker codes in the US, it specifically targets 242 US-listed companies of Chinese origin that have long been reticent to subject their financials to the same accounting inspection as US firms. China’s Securities Regulatory Commission and US regulators have been working towards a compromise to reconcile Chinese and international accounting standards for a few years, but so far, the efforts have not produced a concrete solution.

Even before the most recent legislation, souring US-China relations under the Trump administration had prompted economic uncertainty. For mature US-listed Chinese internet companies looking to hedge their capital footprint in a geopolitically polarized environment, a second IPO in Hong Kong emerged as a safe harbor from uncontrollable geopolitical tensions.

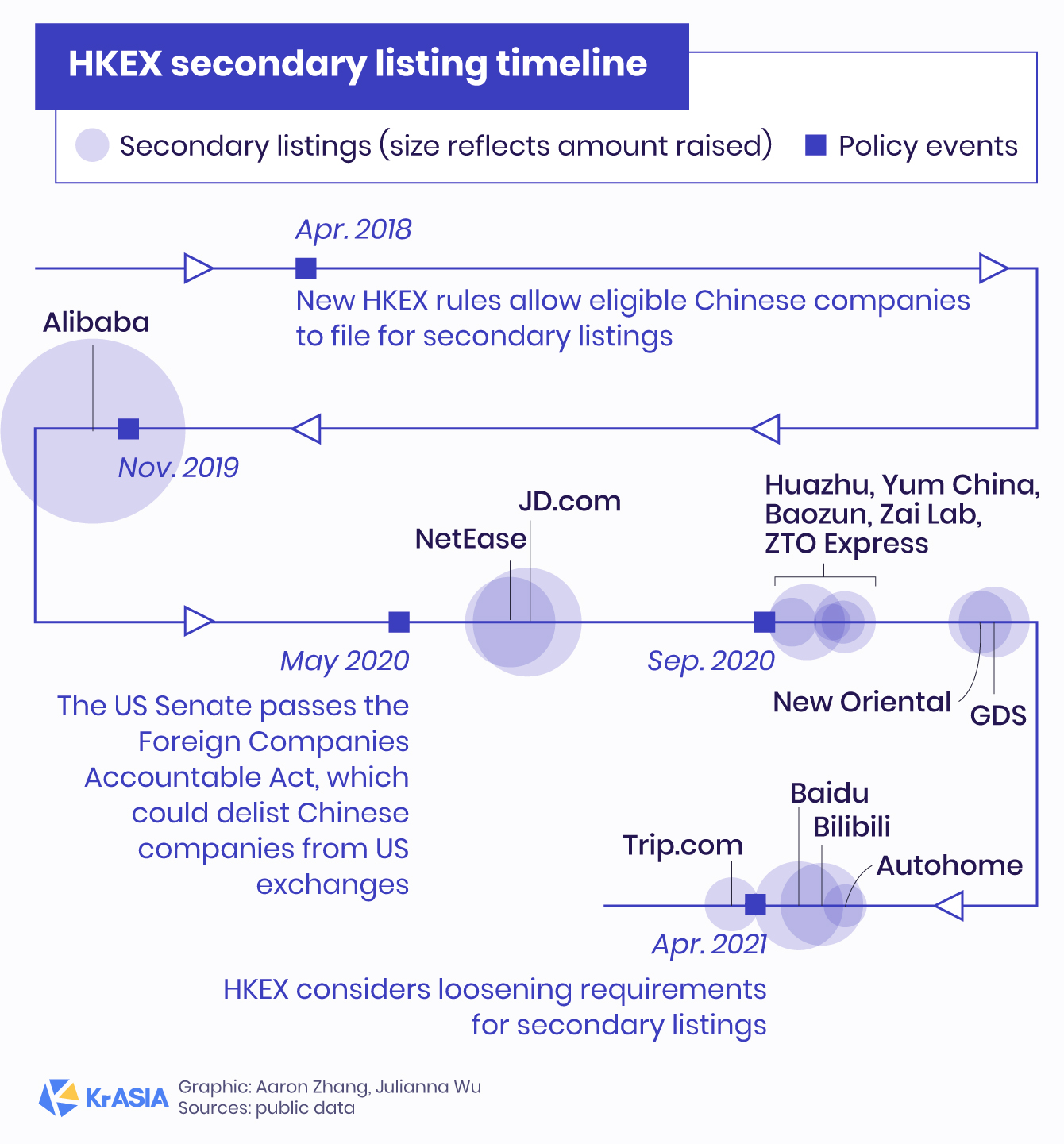

Secondary listings really kicked off in November 2019, when Alibaba raised USD 13 billion in a Hong Kong IPO. Since then, other big names like Baidu, JD.com, Bilibili, and NetEase have followed suit, enabled by the Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s (HKEX) relaxation of rules in April 2018, allowing companies with VIE structure as well as ticker codes abroad to file for secondary listings on the bourse, followed by a subsequent extension of the policy announced in October 2020.

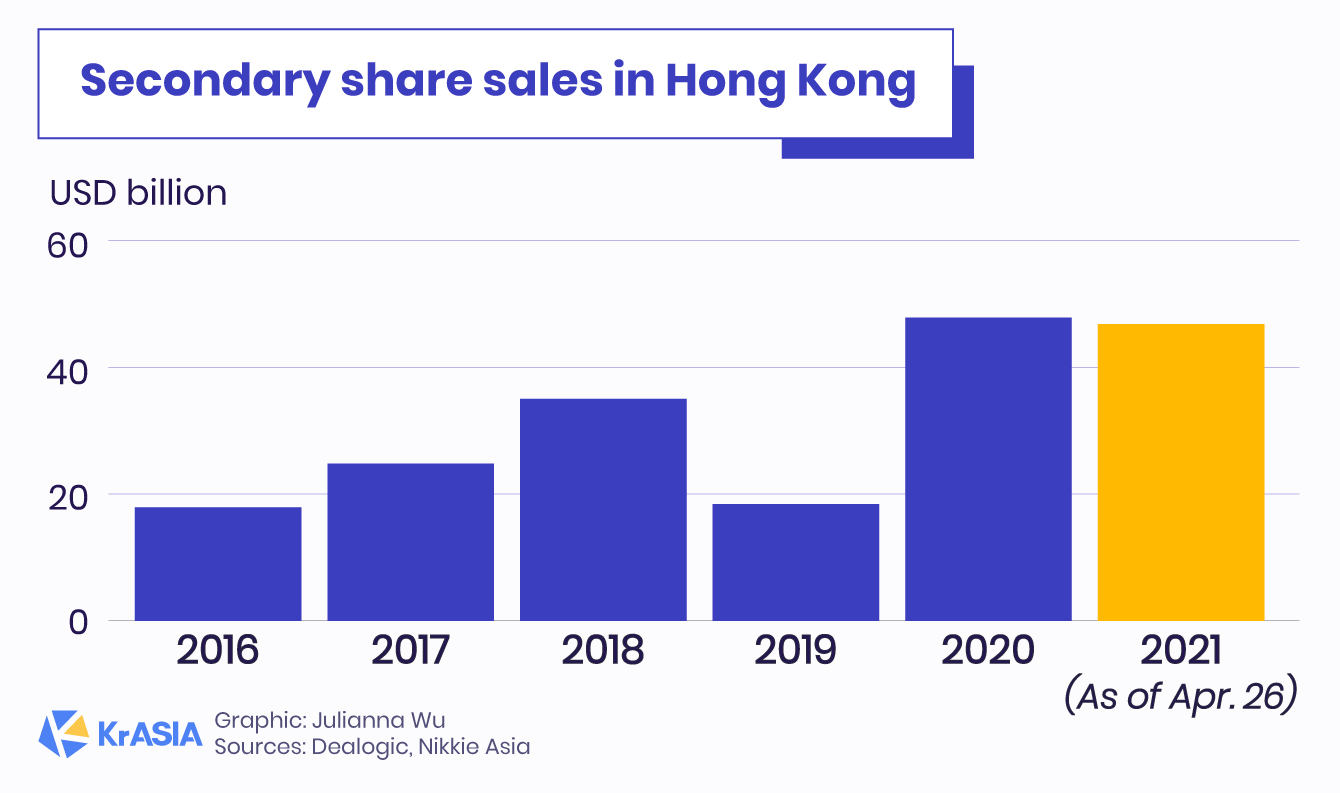

This has created a pipeline of IPOs well into 2021, with more Chinese tech firms tapping into Hong Kong’s capital markets and giving the stock exchange its best-ever Q1 results. Generating a total capital raise of USD 37.3 billion from IPOs since Alibaba’s IPO in 2019, secondary listings have buoyed Hong Kong’s status as a global financial center, even though not all secondary IPOs have performed well.

Slowing investor momentum?

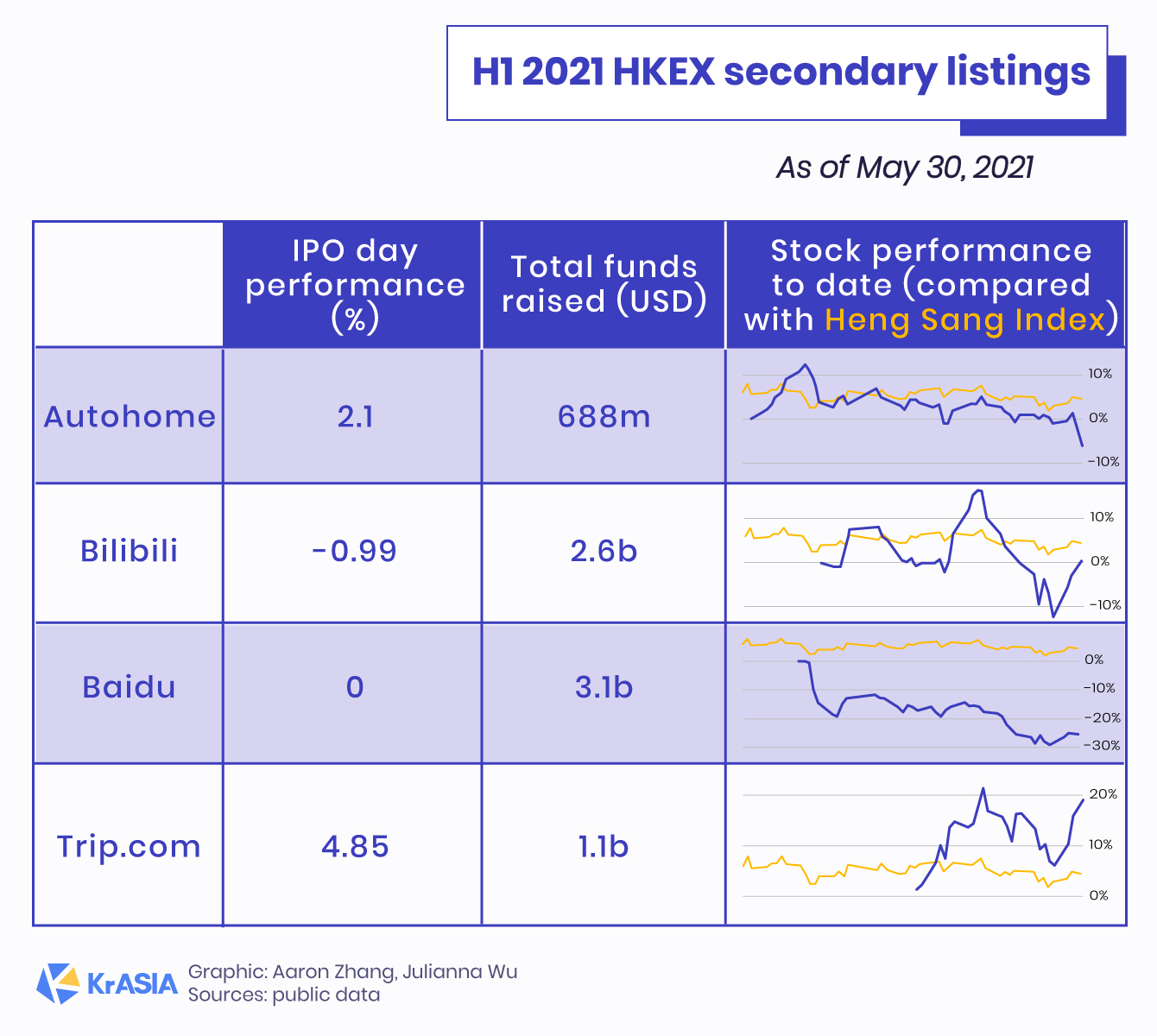

While the nine Chinese tech firms’ to execute secondary listings in 2020 saw their share prices rise by an average of 7.2% on the first day of trading, both Baidu and Bilibili’s secondary listings this year received icy receptions in Hong Kong.

Yet that may just have been part of a broader slump in the market this year. “The investors are not necessarily less enthusiastic. The overall capital market performance hasn’t been good this year, not just for any single stock,” said a KrASIA analyst. Despite some underwhelming debuts, all secondary listings except Baidu have outperformed the Hang Seng Index.

While investor appetite may have waned, more US-listed companies are queuing up for new stock codes in Hong Kong, including Tencent Music, Vipshop, and Joyy Inc.

“Poor overnight stock performance in the US could lead to direct consequence for the companies’ secondary debuts, and pricing will inevitably be set lower than the companies’ highest targets,” the KrASIA analyst added. Bilibili’s US stock price suffered in the lead up to its Hong Kong IPO, with CEO Chen Rui blaming poor timing—his company’s new development coincided with the US Securities and Exchange Commission announcing the implementation of tighter accounting standards.

What’s driving the homecoming?

“The main purpose of a secondary listing is to ease geopolitical uncertainties, to broaden investors’ reserve, as well as to raise new capital,” Xu Xiaohui, managing director of China Renaissance Capital, told Capital Detective.

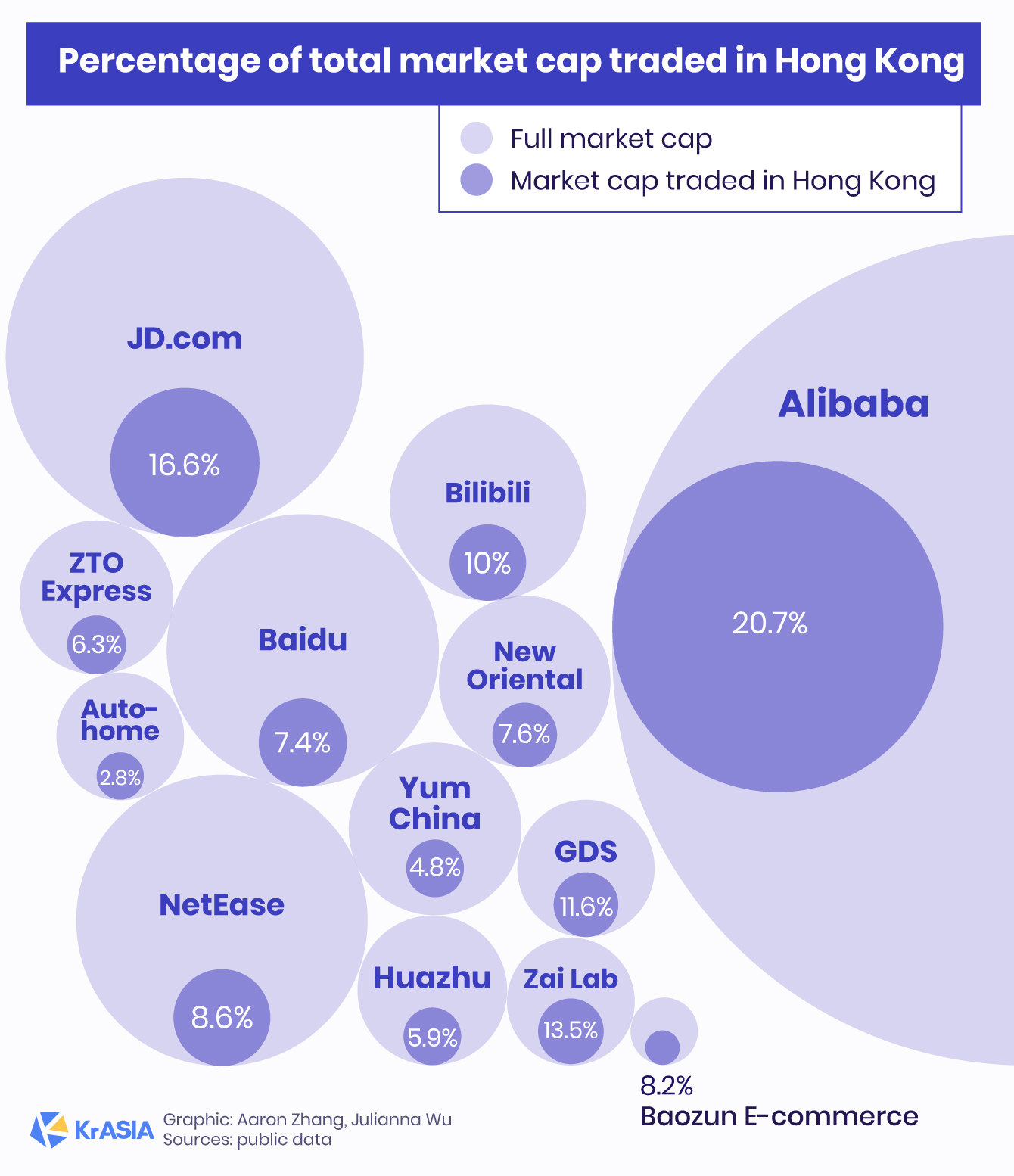

Among these objectives, fundraising is probably the least important. Thanks to market cap requirements, companies that are eligible for secondary listings in Hong Kong are already sizable, established players in their respective industries. These corporations are only allocating at most 20.7% of their total shares in the Hong Kong-listed entity, according to public data.

Furthermore, secondary listings represent a new stage of development for Chinese companies and an opportunity to rebrand themselves. Some have introduced new initiatives when their shares become actively traded in Hong Kong.

Baidu is one example: the search engine giant landed on the Nasdaq in 2005 as “the biggest Chinese search engine in the world.” It still holds that title, but as mobile internet thrives in the country, Baidu has failed to keep up with its peers. In May 2020, both Alibaba and Tencent’s market cap were 16 times higher than Baidu’s.

But this year, Baidu described itself as a “leading AI company” in its prospectus filed to the HKEX, highlighting new business segments, including autonomous driving and industrial internet services.

Hong Kong over Shanghai

In a document released in March 2018, Beijing opened the possibility for US-listed Chinese companies with VIE structures, like Xiaomi, Meituan, and Alibaba, to dual-list their shares on mainland China’s capital markets.

However, obstacles still exist as the RMB 200 billion (USD 28.6 billion) market cap requirement, in contrast to HKEX’s HKD 40 billion (USD 5.2 billion) prerequisite, kept nearly 95% of the US-listed Chinese companies away from the bourse in Shanghai. Furthermore, regulators are still hesitant to accept companies with complicated VIE structures.

Xiaomi originally planned to go public in both Hong Kong and mainland China’s A-share market in 2018 but abandoned the latter after the China Securities Regulatory Commission sent 84 queries to the company, according to a LatePost report.

What does the future hold?

Aside from broader market performance and the geopolitical situation, there are other factors that could affect secondary listings in the near future, such as whether “homecoming” stocks can be included in the Hang Seng Index.

“The companies care much more about whether they are included in the Hang Seng Index than their debut day performance,” said the analyst. “Hong Kong investors, especially institutional ones, love to follow the index. If ever included into the index, investors’ constant, big-amount trading would support the stock prices in the future.”

Another determinant is the HKEX’s secondary listing requirements. While Hong Kong’s stock exchange is more open than Shanghai’s, it still maintains a relatively high threshold for the 240-plus listed Chinese enterprises to leave New York for their homecoming.

Overall, H1 2021 has been a continuation of last year’s series of secondary listings, said KrASIA’s analyst, as almost all eligible companies have already submitted their applications.

Intent on capitalizing on this development, the HKEX is on its way to reforming its rules, with a consultation document published in early April, suggesting that restrictions on secondary listings may be substantially relaxed in the future.